Making products under uncertainty

This article is a follow-up to my talk. You can watch the video recording of the talk in Russian or in English:

Established companies build products according to specs. That’s turning words into mockups and code. It’s easy.

Startups and innovation teams don’t have specs, only vague signals from the market. They zero in on the need, find a product that might satisfy that need and build it. All by themselves. If they get any of the steps wrong, they start over. That’s costly and unrewarding.

Those two modes of operation: research and execution, are different in nature, but we treat them the same way.

I’d like to talk about the research mode. About the mental model and the techniques developers and other members of a team can use to iterate on an idea faster. But there’s a cost, of course. For this new process to work we’ll all have to become rookies again.

Status Quo

We waste time, effort and resources on building stuff no one wants.

I often see teams relying on the product manager to come up with a feature proposal and a spec. The spec then goes to designers. They produce high fidelity visuals and pass them to developers. Devs implement the feature. QA and product verify that it works as expected and the code gets into production.

The process takes two to six weeks on average for large features. A couple more weeks to a month to gather feedback from customers. It’s fine to spend this time if all product assumptions are correct.

It’s a huge waste if Product is wrong.

Why do that?

A couple months of work of a team is about €40K (cost to company) in Berlin. Plus opportunity cost of time wasted. Plus negative impact on the team’s morale. Plus time to maintain added code in the future.

No one wants that outcome. Why are we working towards it? Because we want to do our jobs well:

- Product wants to best utilise the time the team has. So they come up with features and long-term roadmaps so the team can keep building. They often base those on a lot of guesswork;

- Designers want to produce high-fidelity mockups, so developers don’t waste time guessing and the product looks good in the end;

- Developers want to write clean code, have a good foundation, build things that are easy to extend and maintain;

- QA wants to catch all the bugs before they get to production.

We are experts, that’s what we do. In some contexts, it’s appropriate. Like when we know exactly what the customer wants, we have enough time and budget. But in the context of high uncertainty, it’s equivalent to building a high-tech space rocket and launching it in a random direction.

Stop being an expert

Philip Tetlock in his book described a series of forecasting tournaments. The goal of those tournaments was to show how good are experts at predicting the future.

Experts assigned probabilities to various global events: from interstate violence to economic growth to leadership changes. Later those predictions were scored according to how close to reality they were.

In the end, it turned out that experts performed worse than sophisticated dilettantes. Worse even than algorithms that extrapolated from the past.

Experts are quick to jump to conclusions. They are more invested in those conclusions, less likely to change their view. That means that to be better at doing research we need to become rookies again:

- Experts know what they need to do, rookies need constant feedback;

- Experts design architectures, rookies are happy with the easiest way to something that works;

- Experts can justify whatever conclusion they convinced themselves of. Rookies don’t get hung up on conclusions;

- Experts have a reputation to lose, rookies don’t.

We also need to change the focus. Our target during research is not to implement a feature, but to reduce uncertainty. To answer these three questions:

- What to change to achieve our goals as a team?

- What to change to?

- How to make the change?

Again, actually making the change is not the goal of a research.

Example from Polychops

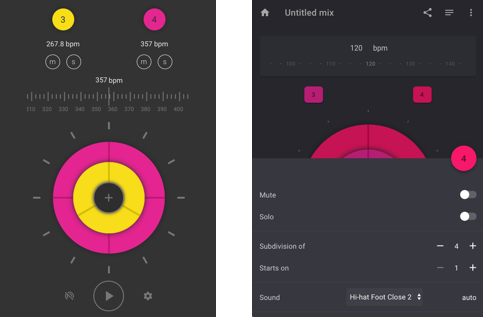

Polychops started off as a metronome for practising polyrhythms. It had an unusual presentation. It worked in a different way compared to other metronome apps and websites.

Before we started working on the project we had a ton of questions:

- How will people react to this new presentation of a beat?

- Can we make it sound good?

- Can we make it look good?

- Are people even interested in polyrhythms?

Getting answers

Sometimes we can answer some of those questions using existing human knowledge. Often times we can’t. In those cases we can use the good old scientific method. We put forward a hypothesis, run an experiment and analyse the results.

How to come up with a hypothesis? Here are several links to get you started: Design Sprints, TRIZ, Current Reality Trees.

Here’s the bird’s eye view of that process:

Find the root cause that prevents us from achieving the goals;

Find an intervention that will eliminate the root cause;

Run an experiment to test that the intervention works.

We’ll focus on Step 3, running the experiment. In software companies, an experiment will often be a prototype.

Prototyping

Prototypes are neat. First, they help us verify our hypothesis. Second, they provide insights into the later stage of the implementation.

Prototypes work well to understand customers’ needs and the shape of the product. They are not good for researching the market. For instance, its size and demographics.

Sometimes we can integrate the prototype into an existing product. Often times we have to start from scratch or fork the code.

The best prototype is the one that we can build and use in the shortest timeframe.

And remember, we have to become rookies. We have to have that beginner mindset when working on and using the prototype.

Seek feedback

A prototype is just a tool for running an experiment. The actual purpose of an experiment is gathering feedback. It’s important to think about how are we going to gather it before we start prototyping.

Example from Productive Mobile

With a B2B product where the sales cycle is at least six months. Besides, our customers are busy people, it was hard to get timely feedback. We worked around the problem by forming a separate team that was using the product in-house. Our internal customer. It was not an easy decision, but in the end, it had a huge positive impact on the product. We’ve shortened the feedback cycle and started moving at light speed.

Example from Polychops

With a B2C product, we’ve tried a lot of different ways of getting feedback. The first round was from friends musicians. Later posts on Reddit, which, in turn, lead to one-on-one interviews.

Qualitative feedback gives more insights. The more outlandish the product idea, the less useful the quantitative data will be. Observe people using your prototype. It’s insightful and motivating.

Example from Booking.com

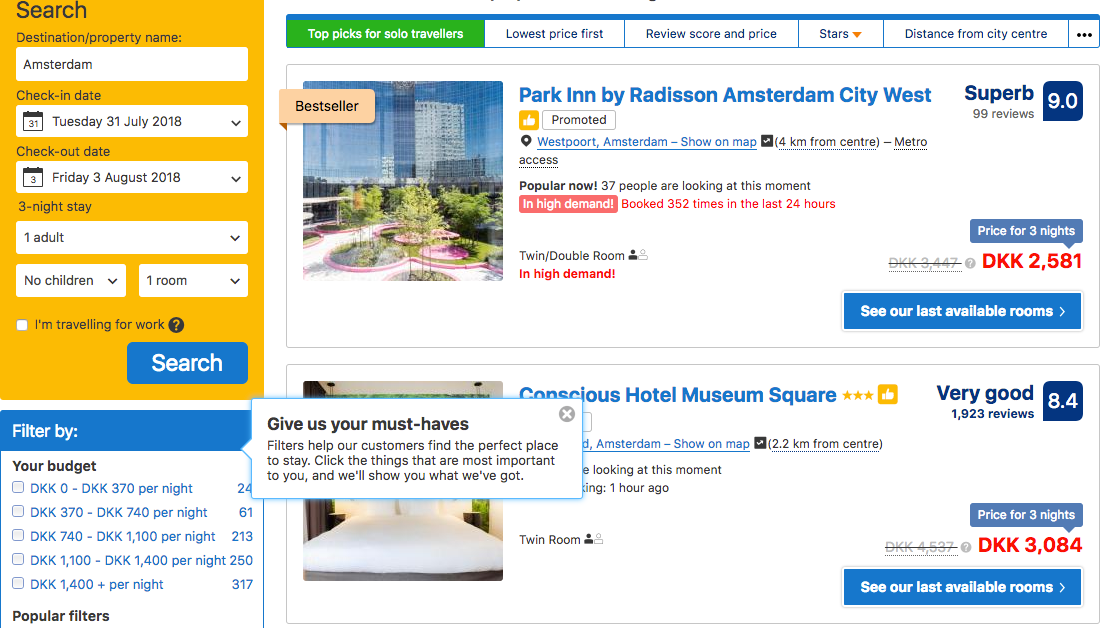

Booking.com famously runs many A/B tests on the site. They are data-driven. I would argue that that’s what’s pushing the site into the unusable abyss.

Example from Polychops

The whole idea of the recording mode in Polychops was born out of feedback. A person wanted to export the audio of the beat to use it in their DAW and record themselves playing on top. We confirmed later that a lot of musicians record and listen back to themselves. So we decided to make it part of the metronome. The feature was born out of talking to people.

Start with the interface, fake the rest

A prototype is an illusion. It’s like a movie set or a theatre stage. We want to make the customer believe that it’s real, without making it real.

The interface is what your customers use, hence it’s the most important part to get right in the product. When prototyping it’s often the only thing that matters.

For UI products we’d map the user flow and create low-fidelity paper mockups. Then we’d use a combination of coding and drawing to build the experience that we want to verify. It’s ok to have some of the parts of the interface not working. But it should look realistic and get the point across.

Example from Polychops

An early prototype of Polychops was a tiny flash animation. We showed it to musicians of different levels to see their reaction, to see if it helps in understanding the concept of a polyrhythm.

The same approach works for API products. We’d start with writing documentation for the API. Then we’d try it out “on paper” on different usecases.

Example from Productive Mobile

We were rethinking our visual mobile app builder. To give more flexibility to the creators we decided to introduce a new low-level API. To prototype it, we first came up with all the methods, their input and output signatures. We then used this new API on paper to verify that it would cover the usecases we were after. We’d write the code that calls the API and then we’d hardcode results of those calls.

Prototype puts focus on the interface, so “backend” becomes something we can fake.

Example from a friend

A friend of mine once told me that it takes their team two to four months to build a prototype and run an experiment. He works in a consumer-facing web platform. Turned out they are often blocked by the backend team. Their decision? To rewrite parts of the backend to use the new micro-service architecture. Although I’m happy for the backend team, it was completely unnecessary to run an experiment.

Example from Polychops: Authentication

At some point, we wanted to let users on the platform interact with each other. To do that the prototype would need some kind of auth. But writing code for authentication and authorisation is a low-impact high-risk expensive task. To not waste time, we implemented auth on the client. A browser would generate and save a token in local storage and use it to authorise requests. It was fake, but it was good enough to run the experiment.

Example from Polychops: Backend API

One of the calls to our API instead of going to the backend is resolved on the client. We pack a JSON with a result inside the app. We are not focusing on that part of the service right now and static data does the job well enough.

Use a design system

We’ll save a lot of time if we have a robust design system. With it ,we don’t have to design every interaction by hand. It frees up the mental resources and we can focus on the product. Going back to the rookie mindset, the fewer variables we have to tweak, the better.

Example from Polychops

We started the Polychops prototype without any design system. We were coming up with the interface “on the go”. It was ok in the beginning. But as we progressed we needed more and more kinds of interactions: notifications, menus, navigation. Instead of designing it all from scratch we switched to an existing system. It saved time and mental capacity.

Steal

Steal ideas from products you love. Ideally, you want to steal from other fields, not from competitors. Stealing from competitors has little to do with innovation, we already know it works.

Example from Polychops

The inspiration for the recording flow in Polychops comes from existing DAW software. For example, when you record, Logic saves all the takes, so you can choose one later. We did the same.

Technical micro-loan

It makes sense to write clean code when we know the system, its requirements and the ways it can change in the future. We don’t have this information when working on a prototype. Making the code clean so we can throw it away later doesn’t make sense.

Here’re several guidelines that might be helpful.

Avoid refactoring

Copy-paste a piece of code at least 3 times before abstracting.

I often have the urge to abstract repetitions. What I’ve noticed working on prototypes is that it leads to more work down the road. For example, UI components might be similar in the beginning, but as you progress they’ll start to diverge. Prototypes are unstable. Besides, it’s much easier to come up with abstractions once you have all the versions of the thing in front of you.

Don’t write tests

Tests are specifications of expected behaviour. Early on you only have an educated guess about what this behaviour is and this guess is most likely wrong.

Structure the code according to the domain model, not the framework

Frameworks and libraries come and go, especially early on. A domain model is a more stable variable.

For example, if you start using Redux, instead of splitting your code on

- Action creators

- Reducers

- Middleware

Use

- People

- Chops

- Beats etc.

Abstract out libraries and frameworks

The initial chunk of work on Polychops was very client-side heavy. I started off using the component’s state as a data store. Later one part of the state moved into a Redux store and the other on the backend connected via Apollo.

During these transitions, the “dumb” UI components stayed the same. They didn’t know what a Redux store or a GraphQL query is, that logic was in wrappers.

Repaying the debt

If the experiment is successful, we would want to proceed with the implementation. In this case we will have to come back and refactor.

Shortcuts we take borrow the time from the implementation phase.

How to get stakeholders on board

It’s hard to change the way we do things. So if you buy into the model I’ve described, how do you get other members of the team to try it out?

This is a whole other article, but here are several tips to get you started:

What we’re going for is convincing stakeholders to stop pushing for features. If they do, the team can take their time to explore uncertainty;

Understand other peoples’ goals and the pressure they are under. Put yourself in their shoes;

Be around. Product manager and other team members depend on your expertise to understand what’s possible and what’s not;

Explain the value of research. This is your bargaining chip;

Come with a concrete proposal. Start small. One of the ways to try out the new approach is to run an internal hackathon;

If I can be of any help, feel free to reach out!

Summary

When building products there’s time for research and time for execution.

The goal of the research phase is to reduce uncertainty. Uncertainty can be in the product itself, the implementation or the market. During research we can’t use the same techniques we use during the execution phase. It would be a waste of time, money and enthusiasm.

Instead, a good mental model to adopt when doing research is to think like a rookie. That means to seek frequent feedback, fake the unimportant, steal. Encourage and support other members of the team to become rookies as well. Research is not the time for perfectionism.

I hope you could use some of these learnings and I wish one day I’ll be one of your many happy customers!

I’d like to thank @victor_suzdalev for reviewing the draft of the article, as well as Oleg Mokhov and Alexey Ivanov for their help with the talk.