Theory of Constraints in Colour

This is the fourth post in the series “Theory of Constraints in software startups.” If you haven’t read the others, I recommend starting here: part 1.

There are thousands of possible reasons for a piece of software to not perform well. Thousands. How many ways do we have of finding and fixing those issues? One. There’s one way we can do it.

- Choose what is that you want to improve: speed of execution, memory consumption, something else;

- Identify the place in the code where the issue is the most present using tools like CPU or memory profilers;

- Improve the piece of code that you found on step two. Because that piece was performing the poorest, the system as a whole will improve;

- Go back to step 2.

Improving performance of a business or a team is no different. Once we understand the goal of the system, we can find exactly one constraint that we need to control to improve the system as a whole. That was the brilliant idea behind Eliyahu Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints.

A quick heads up. This part of the series is a titbit more theoretical than others. It might require some extra energy and curiosity on your part. Thank you for taking a swing at it, I hope it will be worth it!

Looking for the Constraint

There are metrics that can serve as CPU and memory profilers data for a business. We talked about them in the first part of the series. The two most important ones:

- Throughput or how much useful work does the system complete over a fixed period of time;

- Inventory or how much work is stuck in the system but will be released at some point.

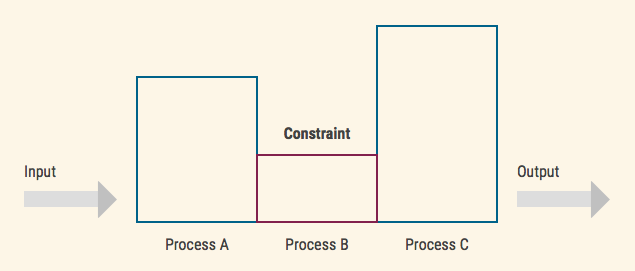

Constraint of a system is a department or process that limits the output of the system as a whole.

In other words, constraint is the element in the system that has the lowest throughput. One of the indicators of a constraint is growing amount of inventory in front of it. Every system has only one constraint (in rare cases two, but never more). If you’ve found more than one constraint, most likely you haven’t defined the system and it’s goal clearly enough.

If we can measure throughput and inventory level of every step of the process, we can find the constraint. But we can’t measure abstract concepts. What exactly are our throughput and our inventory depend on the system and its goal.

Example

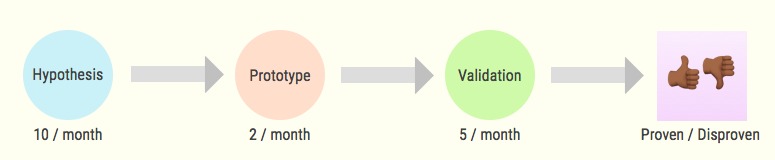

Let’s say we’ve founded a startup and we are doing customer discovery. As an early stage company, our goal is to find a problem worth solving and a viable solution. We work towards that goal using an iterative process of formulating and validating hypotheses.

We know we found problem-solution fit when during interviews 8 out of 10 potential customers are willing to give us something of value. We are looking for some kind of commitment from them — could be time, money etc.

- Throughput of that system is the amount of hypothesis we have validated during one month that improved the score (increased the amount of committed potential customers);

- Inventory of that system is the number of hypotheses we’re working on at a given moment.

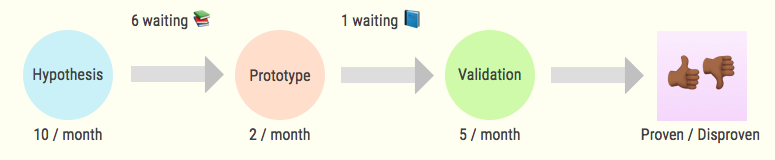

The constraint of such a system is a department or process with the lowest throughput. In our case it’s the “Prototype” stage:

One indicator of a constraint is a growing pile of inventory in front of it, aka a large backlog.

What can go wrong?

By definition, the constraint is limiting production capacity of a system. That also means that only if we manage the constraint well, we can increase the throughput of the whole system.

Finding the constraint was the hard part. By comparison, controlling it is fairly straightforward. We need to avoid these two things:

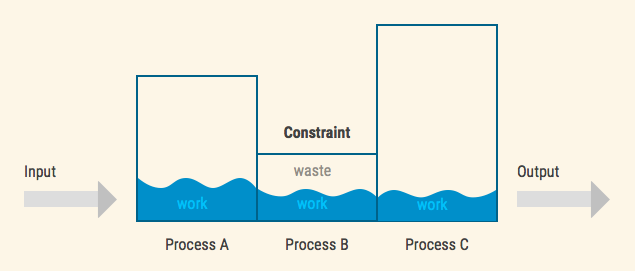

1. Underutilising or “starving” the constraint.

Every other department or process has extra capacity to waste, except for the constraint. If the constraint is not producing useful work, the output of the system suffers;

2. Overproducing or “overloading” the constraint.

If departments before the constraint are always overproducing, the inventory in the system grows continuously. In the previous article we saw what it leads to. Things take ages to complete.

Example

Here’s what we could do wrong in the startup example above:

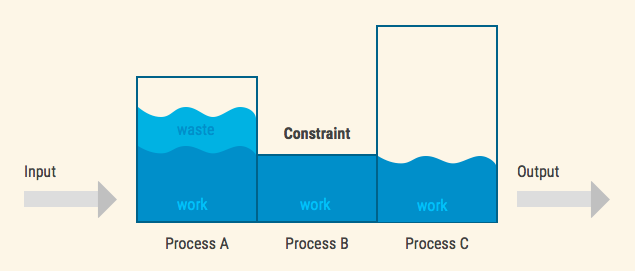

In this process we must make sure that the Prototype phase is never starved. For example, the Prototype Team might be blocked waiting for specifications to build. They could also be doing bogus work validating ideas that could be rejected without a prototype.

The time of the constraint is the most precious resource in any organisation, we shouldn’t waste it.

Overloading the constraint in this example would mean to keep producing hypothesis and stacking them in the Prototype’s Team backlog. What will this company do with a list of hundreds of ideas? Best case it will add overhead to whoever manages the backlog, worst case it will encourage the Prototype Team to multitask.

Improving the flow of work

Goldratt laid out an algorithm that helps us continuously improve any system. He is arguing that before we throw more resources at the problem, it’s important to make sure that we improve the flow of work through the constraint. He proposed these mechanisms to achieve it:

1. Exploit the constraint.

We should make sure that the constraint is 100% utilised. That there’s no downtime due to any reason. That the constraint is doing only useful work.

2. Subordinate other elements of the system to the constraint.

Other parts of the system need to maintain a continuous flow of useful work through the constraint. Often times it means that those parts themselves would be working “inefficiently” in order to make the constraint and hence the system as a whole more efficient.

Example

Even though the “Exploit” step seems straightforward I often see teams fall into the trap of making the constraint wait for resources. The most common example I saw and experienced comes from Engineering.

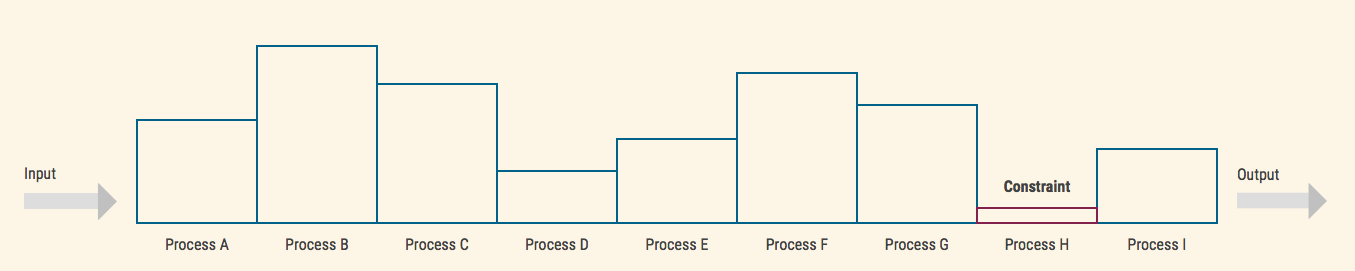

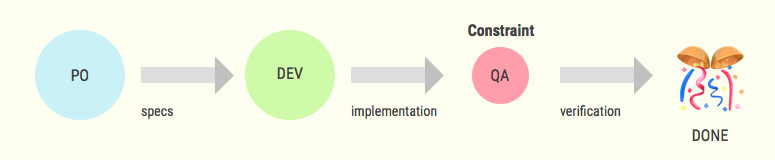

Let’s say our engineering process looks like that, with QA being the constraint:

Let’s say we use Scrum. We select a bunch of features and bugfixes before the sprint starts and then try to finish them during the iteration. The problem is that for the first half of the sprint (until developers implement the first feature) QA will have no useful work to do. The constraint is under-utilised.

Scrum process will hurt this team’s performance.

Now let’s say QA returns 70% of tickets back to developers for rework. That means that QA would have to go through most of the issues two or more times. We can subordinate other elements in the system to help lift some of this burden on our constraint. For example, we can ask developers to test each other’s implementations before they go to QA.

In the last example developers will have to do work they are not qualified to do. Their efficiency will go down, but they are not the constraint, QA is.

In that example by making developers less efficient, we make the system as a whole perform better.

Five focusing steps

In his first book, Eliyahu Goldratt laid out a process of continuous improvement of any organisation. Step zero is to formulate a clear goal. Then we follow the steps:

- Find the constraint;

- Exploit the constraint;

- Subordinate other parts of the system to the constraint;

- Elevate the constraint (give it more resources);

- If the constraint has been broken, repeat.

It’s an iterative process. We find the constraint, try to get the most out of it, add more resources only if necessary and repeat if the constraint has been broken.

The purpose is not to gradually remove all constraints, but to know where the constraint is right now and how we can get the most out of it.

The scariest place you can be in as a business is not knowing your goal and your constraint.

Our experience with ToC has been very rewarding. Initially, we’ve applied it to different isolated parts of the company. First engineering, later product and sales. Gradually we’ve noticed that it works best when applied to an organisation as a whole.

At Productive Mobile we used it to set up health metrics for each team, to structure the product roadmap, and even to remake our sales strategy.

Personally I’m using Theory of Constraints as a mental model to reason through any system. It helps me reduce complexity and focus. It’s been a liberating experience for me.

Enough Theory!

Now that we’ve got the theory part out of the way, I hope to give more examples from real world situations in the next articles. If you have tried ToC yourself, please share your experience in comments.

Till next time 👋

I’d like to thank people that shared their experience and useful insights with me. Their inputs are the foundation of this series. In no particular order, these people are: Stefan Willuda, Ricardo J. Méndez, Ed Hill, Adiya Mohr, Conny Petrovic, Goran Ојkić.