Kanban like it’s 1984

This is the third post in the series “Theory of Constraints in software startups.” If you haven’t read the other two. I recommend starting with those: part 1, part 2.

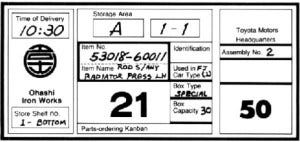

Everything was better in the 80s, so let’s go back in time for a minute. Imagine you are a worker on a plant. The plant is supplying parts to Toyota factories, where they assemble the gorgeous Corolla AE86.

Your shift starts at 7 am. You come to the plant 10 minutes before, change and go to the Kanban storage area. There on your shelf you find one card with the name and the number of the part you will make.

Once the part is done, you put it on the designated shelf and go back to the Kanban storage area. This time there are no cards on your shelf. What happens then is the result of a hundred years of evolution in management. The genius invention of Taiichi Ohno called… actually, I don’t think it has a name.

If there are no cards on your shelf. There are no parts that the plant needs from you at the time. So here’s what you don’t do. You don’t just start running parts that you think you “might” need in the future, you don’t go to managers and ask for work to do, you don’t go help your colleagues do their job.

You do nothing. No-thing. Nada, nichts, nenio.

Just in time

This technique, using Kanban cards to control work on a factory floor, is a part of a larger framework. The framework is called Lean or Just-In-Time.

The goal of Lean is simple — minimize waste. There are different ways to classify waste, but I like to think there are just two big groups:

- Work we did that we shouldn’t have done. That’s wasted resources;

- Work we should have done but didn’t. That’s wasted opportunity.

Let’s say we are managing supermarkets’ supply chain. We are making sure each shop has just enough supplies. It is a tough problem and the solution directly impacts the bottom line of the company:

- Order too much groceries and they expire before we can sell them. We lose money. Wasted resources;

- Order too little groceries and a customer won’t buy what they are looking for. Do it frequently enough and we lose the customer. Wasted opportunity.

Waste is a universal concept. Orders in a supply chain, inventory on a plant floor, product features and bugs, customer projects — all can be a source of waste. Today Lean is used anywhere from a production line to a startup business.

When to turn off the Sales department

Too much work leads to waste, too little work leads to waste, how much work leads to shiny mountains of gold? Enter Kanban.

In a non-kanban process the previous work center decides when tasks get pushed to the next work center. It creates issues down the line where one of the work centers might be overloaded with other projects.

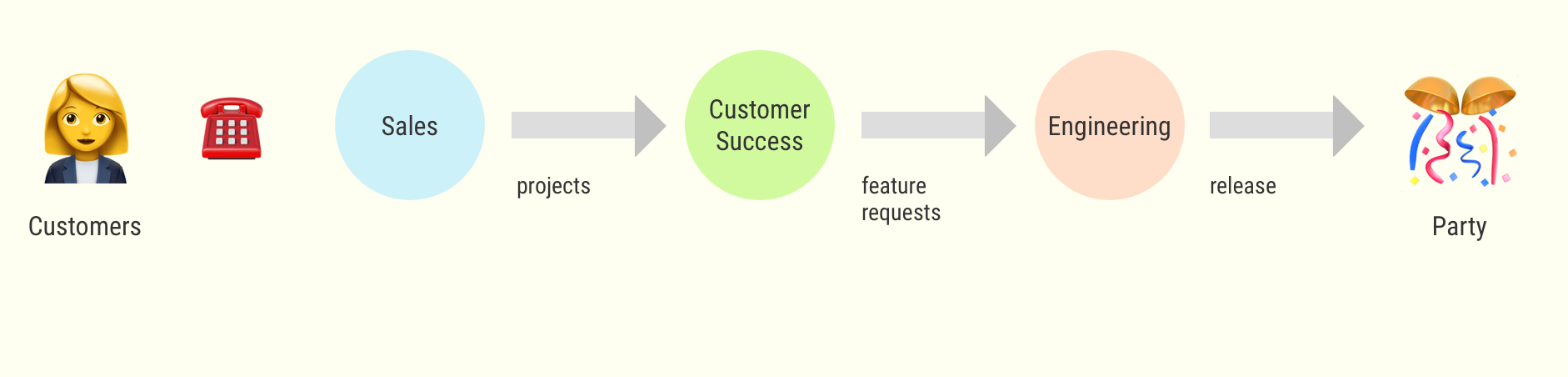

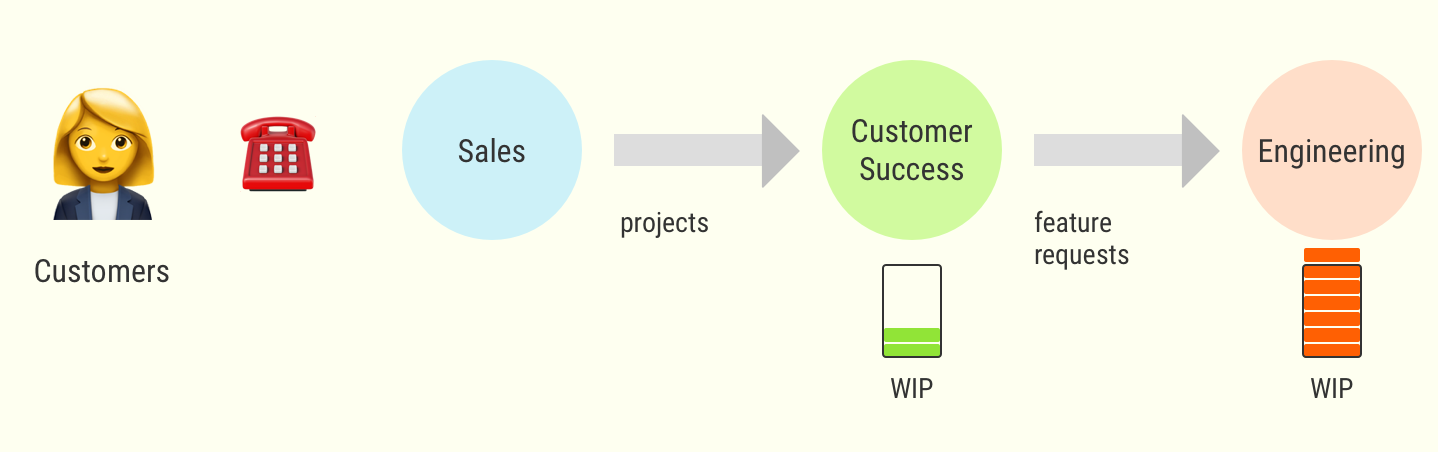

Here is how a B2B startup might handle customers’ projects:

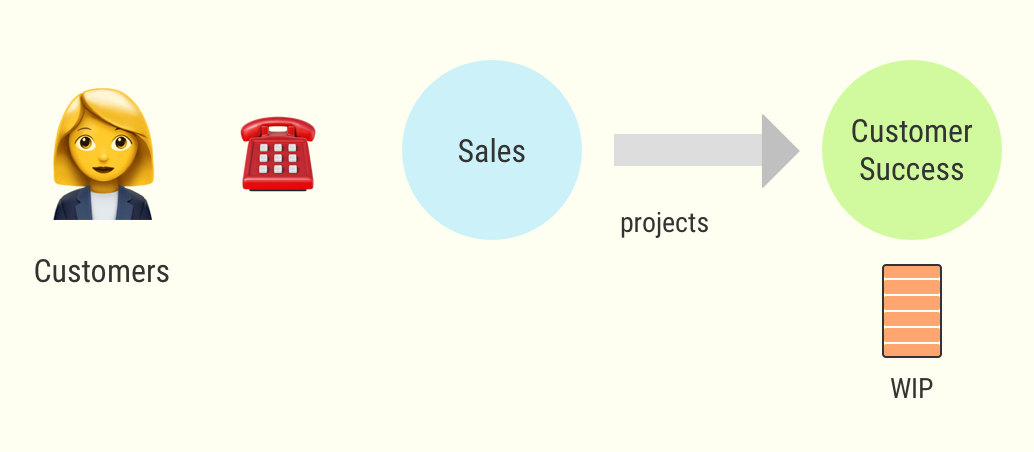

Let’s say a Customer agrees to do a Proof-of-Concept (POC) with us. The worst thing Sales could do is to ask Customer Success team to handle the project right away, without taking into account how much work they already have on their plate:

Let’s say Sales did consult with Customer Success, and those have the capacity to handle the new project. Should we agree to take it?

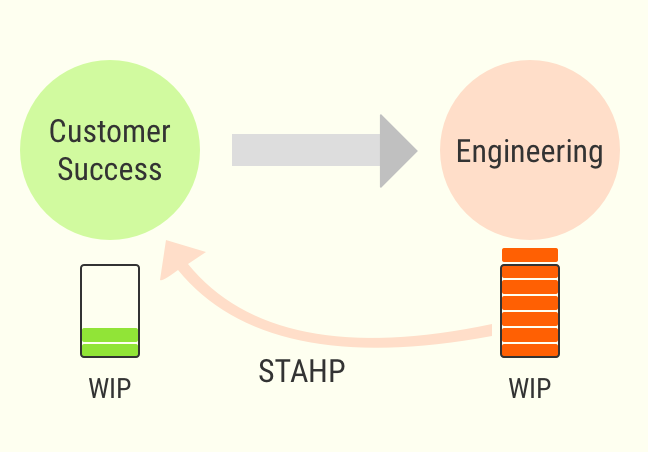

In a non-kanban process there’s no way to know if we can take the project. What can go wrong is that there’s a part of the system down the line that simply doesn’t have the capacity:

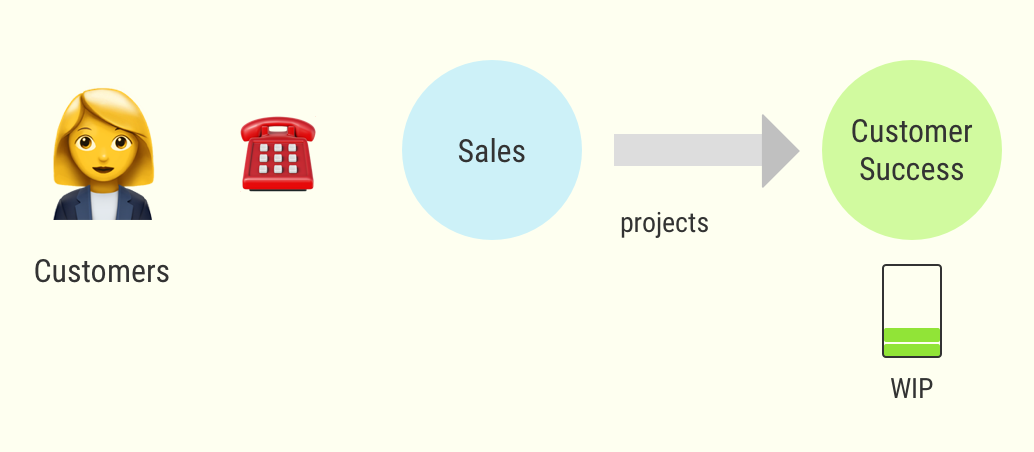

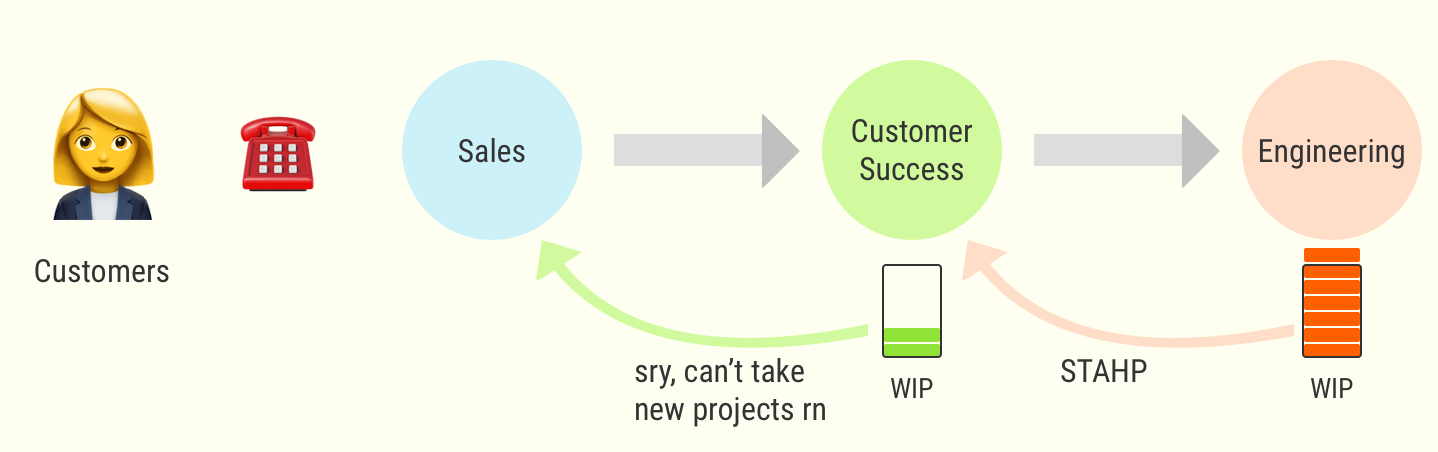

We can fix that organization by creating a feedback loop. We make it so the following work center decides when the work center before should start or stop working.

With that feedback loop we now know when to start new projects so that they don’t spend time waiting for resources.

Let’s take Kanban for a test-drive in our simulation.

Dream team switches to Kanban

In the previous post of the series we saw how our dream-team drove the company into the abyss of ever-increasing inventory and lead times. The problem was that the team was doing too much work.

We can, of course, be wasteful by going radically in the other direction too. Let’s say we start with only one spec every other month when the system can do twenty every week (which there is enough market demand for). In this case we are wasting opportunities by not utilizing the system enough.

Here’s how we can fix the process with Kanban. We have three work centers: Product Owner, Devs, and QA. We will give 13 Kanban cards to QA. They’ll use those cards to “order” features to test from developers. Devs can not start working on a new spec until they have a card from QA. Once they finish a task, they move it to the tester together with the card. Once QA gets back the Kanban card, they can use it again to “order” work from developers.

We’ll do the same with Devs ordering specifications from the Product Owner. Developers will have 7 cards.

I’ll talk later about where those concrete numbers for WIP come from later. First, let’s run the simulation.

Some observations:

- After initial ramp-up of 8 days the team is stable and is releasing every 4 days. After 20 days we have released 24 tickets;

- Often because of the WIP limits PO and Devs are not working at 100% capacity, QA is the only one working at 100% capacity all the time;

- Work in progress never goes above 15 tasks;

- Lead time never goes above 10 days per ticket.

Showdown

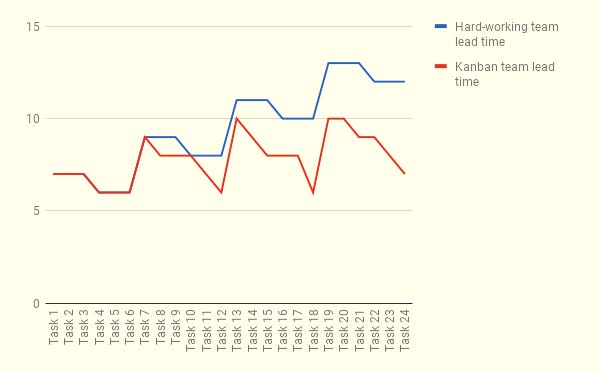

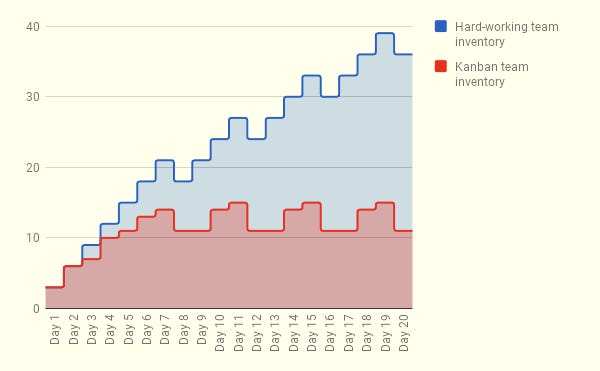

Let’s compare the Hard-working team and the Kanban team over 20 days.

The Kanban team is crushing it! WIP limits helped them take inventory and lead times under control. They can predict and plan with certainty and can finish tasks faster. All of that is possible because they know when to start and stop working.

Why use Kanban

Kanban is a signaling mechanism set up between actors of the system. It notifies them about when to work and when to stop.

Kanban is also an instrument of balance. Once we set the work-in-progress (WIP) limits, the system regulates itself. There’s no need in hands-on control.

We can use Kanban to manage the flow of work in one team or in an organization as a whole.

Here are some of the benefits of this approach compared to just “working hard”:

- The organization is more reliable. We can predict how much time it will take to complete a new job;

- We know which commitments we can and can not make;

- Little to no multitasking, because inventory in the pipeline is limited;

- Less multitasking leads to higher performance and less frustration within the team.

Once we focus on minimizing waste, the effectiveness of the organization goes up.

Why not use Kanban

It all sounds good, but we haven’t yet talked about how to actually set up those work-in-progress limits. This is, in my opinion, Kanban’s weak spot, because:

- Teams’ performance in the real world is unstable and unpredictable, there’s no way to calculate it reliably;

- Each actor in the system will have their own WIP limit. The more actors, the harder it gets;

- On top of that, we have to use different units of WIP for every actor. For example, we can not use developers’ estimations for measuring QA’s inventory. Similarly, Customer Success team will have different units of WIP compared to Engineering.

Setting up Work-In-Progress limits is hard.

Kanban practitioners encourage us to start with something and adjust WIP limits as we go.

To put things in perspective, I had to run the simulation about 10 times on paper in order to figure out actors’ WIP limits and I’m still not happy with results. For example, I know we can lower lead times by changing the WIP limit for Devs. Try it out yourself, if you like.

Summary

We can make an organization more effective if we minimize waste. For that we need to do the right thing, but also we need to be smart about the way we do it.

Kanban is a smart mechanism that makes different parts of the system communicate and balances the work.

Kanban is not easy to implement and maintain because we need to adjust WIP-limits regularly for every work center.

– Andrey, it’s part 3 of the series and you haven’t introduced Theory of Constraints yet?!

I know I know, I’m sorry. Trust me, this other stuff we’re talking about is important. We’ll get to it. Actually, now is a good time to make that intro.

Eli Goldratt built his Theory of Constraints on top of existing frameworks like Lean and 6-sigma during the 80s. His breakthrough idea is that if we want to improve the system as a whole, we don’t need to worry about every single work center. We should focus our attention on a single actor in the system, the constraint.

He understood that no matter how complex the system is, no matter how many parts it has and how intricate the workflows are, each system has only one constraint. We’ll talk about how to use his discovery the next part of the series.

I’d like to thank people that shared their experience and useful insights with me. Their inputs are the foundation of this series. In no particular order these people are: Stefan Willuda, Ricardo J. Méndez, Ed Hill, Adiya Mohr, Conny Petrovic, Goran Ојkić.

Special thanks to Cristina Amate for the illustrations as well as her support and early feedback on the talk and articles.